Julie Curtiss is really into painting hands. These hands, often central to her densely pigmented surrealist paintings, are manicured, mangled, and a little bit beastly. “I’m interested in archetypal images,” she says, referencing Carl Jung’s theory of archetypes and our unconscious pattern of categorizing. In particular, she’s interested in portrayals of domestic life in the ’50s and ’60s, with the advent of home appliances: “The idea of the housewife who gets manicures because she doesn’t need to use her hands.” And while this archetype was far from any female reality Curtiss grew up with in Paris (she was raised in a family where typical gender roles were reversed), it’s one that fascinates her. “These hands are not mine, and that’s why I’m attracted to them,” she says. “I’m attracted to this other possible narrative.”

The narrative in Curtiss’s work, while left intentionally vague, explores the many dichotomies of the female experience. “I like to play on the dualities of nature and culture, attraction and repulsion,” she says.

Become an S Insider

The latest in fashion, beauty, design, and arts & culture.

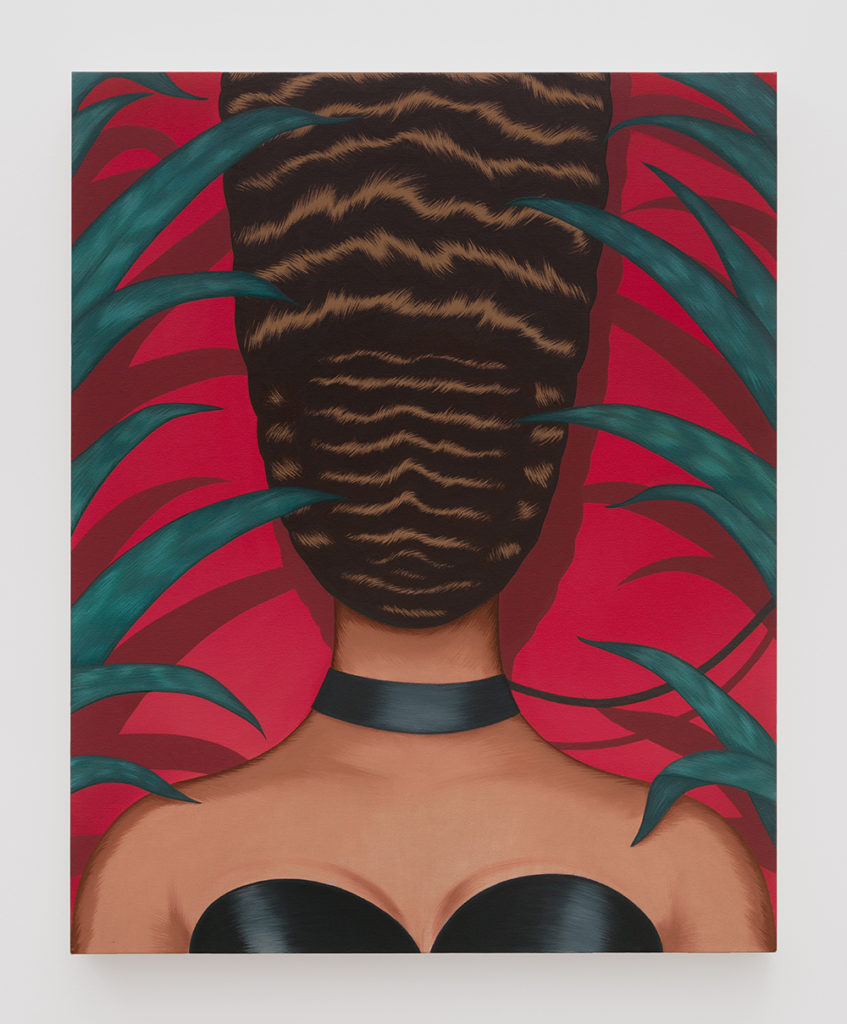

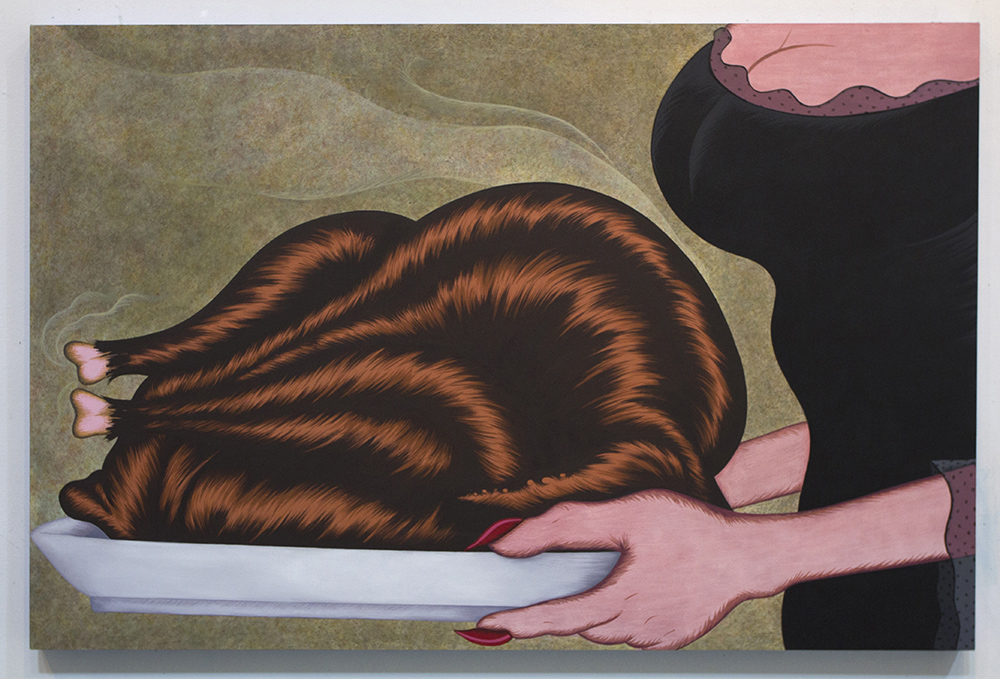

To that end, she disassembles the female body, reimagining it in surreal, alternative realities. For instance, in Her Master’s Voice, Curtiss paints a woman whose face is completely obscured by gleaming curls. Little else is visible, save for a leather choker and corset top. “It’s about belonging to someone,” she says. “As much as we complain about gender roles, sometimes, the idea of ownership is not altogether unpleasant.” In No Place Like Home, similarly shiny locks of hair are wrapped around a roasted turkey and served on a platter by a woman with visible cleavage and a bright red manicure.

Hair is a frequent motif for the artist, who incorporates it into acrylic and oil paintings, gouaches, and experimental sculptures. “For me, it’s something that relates to both nature and culture,” she says. “When it grows on a woman’s body, it’s considered bestial, but when it grows on her head, it’s beautiful.” If Curtiss is unsettled by this contradiction, it doesn’t show. Case in point, Ice Scream, which depicts a furry soft-serve shell for the legs of a sea creature, and is as subversive as it is appetizing.

Curtiss’s sculptures, which feature wig hair that has been braided or layered onto curious hat-like forms, often accent her exhibitions, including her recent solo shows at Anton Kern in New York and Various Small Fires

in Los Angeles. They make up a small but integral part of her practice, which is rooted in exploration and physicality. “Early on, I was able to get very engrossed in the process of making things. I loved disappearing in my own head, being, as they say, ‘in the flow,’” she says, recalling a trip to Vietnam in her teens. “I just sat somewhere for an hour and drew everything around me. It was a different way to interact with my surroundings—I didn’t need to participate; I just absorbed.”

Today, Curtiss is inspired by her surroundings in Brooklyn, where she lives and works with her husband, a fellow artist. “Whenever I bike in New York, I’m captivated by street scenes,” she says. Her next series will be large in scale to mimic the city’s bombastic energy. “I love the high buildings of Midtown, I love the beauty salon. Sometimes, it feels like you are travelling in time.”

Photos courtesy of Julie Curtiss and Anton Kern Gallery.